Thoughts on the article “Are chatbots of the dead a brilliant idea or a terrible one?”

I’ve just read this article: Are chatbots of the dead a brilliant idea or a terrible one? It was one I’d saved because the Black Mirror episode I saw years ago had really stuck with me. In fact, it’s mentioned in the article — so not just me then! My thoughts are at the end, after some excerpts:

To some, chatbots of the dead are useful tools that can help us grieve, remember, and reflect on those we’ve lost. To others, they are dehumanising technologies that conjure a dystopian world. They raise ethical questions about consent, ownership, memory and historical accuracy: who should be allowed to create, control or profit from these representations? How do we understand chatbots that seem to misrepresent the past? But for us, the deepest concerns relate to how these bots might affect our relationship to the dead. Are they artificial replacements that merely paper over our grief? Or is there something distinctively valuable about chatting with a simulation of the dead?

Although chatbots have been around for a long time, chatbots of the dead are a relatively new innovation made possible by recent advances in programming techniques and the proliferation of personal data. On a basic level, these chatbots are created by combining machine learning with personal writing, such as text messages, emails, letters and journals, which reflect a person’s distinctive diction, syntax, attitudes and quirks. There are various ways this combination can be achieved. One resource-intensive method involves creating a new chatbot by training a language model on someone’s personal writing. A technically simpler method involves instructing a pretrained chatbot, like ChatGPT, to utilise personal data that is inserted into the context window of a conversation. Both methods enable a chatbot to speak in ways that resemble a dead person by ‘selectively’ outputting statements the person actually wrote, ‘generatively’ producing novel statements that bear some resemblance to statements the person actually wrote, or some combination of both.

Like memoirs, photographs, letters, hats and oral histories, chatbots of the dead can serve the manifold goals of our memory quests, giving context to our lives, relationships and identities as they help us forge connections across time

the potential of these technologies would be better understood if they were thought of more like artworks – or, rather, like theatrical performances. Engaging with a chatbot is a lot like attending a participatory theatre performance. In these performances, audience members play active roles in the story.

Imagine that you collaborate with engineers to create a chatbot of your deceased grandfather. You decide to build a selective chatbot to memorialise him via sentences he actually wrote or said. But you want the conversations to flow smoothly, so you include some generative functionality. You embark on the laborious task of deciding which salvaged writing to include in the dataset. It quickly becomes clear that sentences from cover letters are written in a professional voice that differs from the intimate voice of family letters. You also have audio recordings, but your grandfather’s spoken voice is different from the way he writes – a person’s multitudes are not easily sortable into clear categories.

If these tools are made to serve artistic goals, rather than commercial ones, the attachments they foster will be nourishing rather than addictive.

It’s been over a decade since I last heard my parents’ voices. My day-to-day sense of loss, and the need to externally integrate them into my life in this way, is no longer as sharp. I still hear my dad’s voice internally when making decisions.

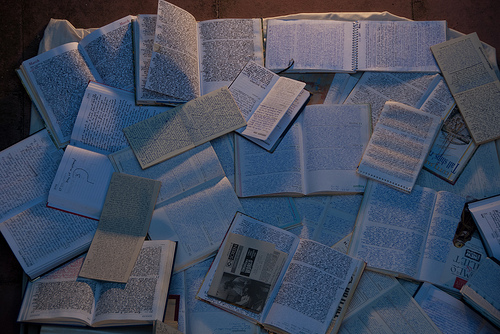

Over recent weeks, while sorting through the memory boxes in the loft, I’ve realised how little of Dad’s “output” I have — an occasional appointment diary, a piece of metal shaped into Snoopy that he made using a machine at work. Dad didn’t leave much that I could feed into a chatbot.

Mum did.

I have a couple of decades’ worth of journals. The later ones are very focused on the day-to-day minutiae of their shared lives — who got up first, what they had for breakfast. There’s little emotion in them. But at least for the first decade, they are her words. If we analysed them thoroughly, perhaps we could pinpoint when dementia first started to eat into her brain. I’ve often wondered about this.

I also have school reports for her, and reflections from friends that they kindly shared so I could pass them on to the care home she lived in during her final few years. These help build a more external view of her life.

When she was in the care home, and I was her connection to her previous self, I might have considered feeding these things into a chatbot to help me make appropriate decisions on her behalf. I created a Twitter account to share her diary entries, 30 years ago today, which kept her previous self a little more present in my everyday life — so maybe I’d have found emotional value in a chatbot too.

As I said at the start, I found this to be a really interesting article, and reading it while on holiday has given me the time to digest and respond to its ideas. I’m grateful for that.